22 Apr Growing Pains 4: Motherhood

By Beth Livingston

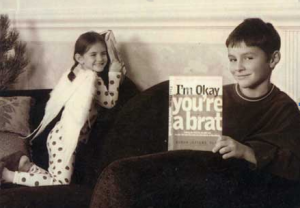

Lila and Parker, the author’s children.

Months after the car accident that left me paralyzed, my husband gently revisited the subject of having children. I had always assumed we’d have one—or many. “Things are different now,” he said. “I would understand if you didn’t want to have kids.”

Things were different, I thought. I likened my paralysis to a small child that would never grow up. I would always struggle to dress it, potty train it, and check and care for “owies.” I already felt overwhelmed by the care my paralyzed body required and wondered if I could handle the stress of caring for the body of another.

Two and a half years after my accident, however, I gave birth to my first child. Parker arrived with little fanfare and landed into the open, loving, nervous arms of his parents. After three months of sleepless nights and restless days with a colicky baby, Parker suddenly grew into a disarmingly charming toddler. I had managed to develop a set of survival skills and, even more necessary for a newcomer to Montana whose family was 2,000 miles away, a network of good friends and babysitters. Motherhood had taken hold of me.

Just as we began to enjoy having a toddler who took thankfully long naps between bouts of “busy-ness,” the “there’s never a good time to get pregnant” plan kicked in again. I was running a store, taking care of a home and a child, and now, increasingly exhausted by my second pregnancy. Occasionally sleep came for me, outside Parker’s prescribed “nap times,” and I would wake to find him missing. Fortunately, he survived his misadventures––the worst being a trip with his dog Norton down to the not-quite-dry creek bed on the edge of our property, where his tiny legs were mired in mud up to his calves.

As a mother, it is impossible to trivialize these unforeseen events and accidents waiting to happen to your babies. It is scary to feel completely responsible for someone so vulnerable in an endlessly dangerous world, scary to love another so completely in defiance of the danger.

My second son, Waters, was born on January 27, 1994, when Parker was three. He was welcomed into our tribe without incident. We did not find him being wrapped up by his brother in an attempt to “give him away,” as my brother had done with my sister. Parker welcomed Waters as a playmate and confidant.

Waters’ increasing command of the English language and ability to take directions made him even more useful during play than the dog.

On Monday, January 16, 1995 my husband dropped Waters off at the in-home daycare that had cared for him since he was 4 months old. It was Martin Luther King Day, 11 days before Waters’ first birthday.

Around 3 p.m., I received a call from a nurse in the emergency room at our local hospital. Something had happened to my son, she said, and I was to come as quickly as possible. She would not go into details over the phone, repeating only that the doctor would explain what had happened once we arrived. I scrambled into the car and began chain dialing the ER on my cell phone, which kept cutting out due to poor reception. The nurse stood her ground, repeatedly stating that the doctor would explain the situation. Finally I demanded: “Is my son still alive?” Silence was the only response. I began to wail, and hung up the phone.

My son died during a nap that day. It was not considered SIDS—sudden infant death syndrome. He was too old. His death was listed “undetermined” after an exhaustive pathology exam.

Nine months after his death, my daughter Lila was born. I saw her in a dream before she was born and I spoke to her. She was the most beautiful girl I had ever seen, and she had a tiny “angel bite” over her right eye. When I woke, I told my husband all about our baby. It was a girl, she was a beauty, and she would have a tiny mark above her eye at birth. At his skepticism, I replied only, “You’ll see.”

Lila was born as I had seen her. A beauty, kissed by angels, and endowed with her brother’s soul. Waters’ death and Lila’s birth taught me many lessons about motherhood. I wondered if love could be extinguished by grief, but I found that love is an opportunistic emotion; it blossoms even in the most inhospitable environments. It taught me that life could be both rich and full, no matter how short.

It also taught me that life is too short and too precious to live with fear. It seems that love is having the courage to love so deeply that it might just break your heart.

Beth Livingston is the mother of a two children. She lives in Bozeman, Montana.

No Comments